Murky fields of imposition. The case of a systematic review

Convenors’ preface

We hope the story that follows will be the first of several case studies from Big Push Forward supporters about how results and evidence artefacts are used in the politics of evidence. It shows how the methodological utility of an artefact has to be discussed in relation to the process and context of an artefact’s uptake. In this case the politico-managerial environment is one in which hidden and invisible power determine which knowledge counts and hierarchical ways of working (in both donor and recipient organisation) block communications and con sultation.

sultation.

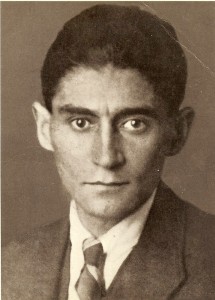

Anonymity in this case has been protected through changing the policy question that was to be reviewed and by providing pseudonyms for the donor agency and the research organisation that feature in the account. The author calls himself Joseph K, pharmacy because, as he emailed us, he felt like the character of that name in Kafka’s stories that are full of rumour and hearsay and where there are no villains. Everyone stumbles around as in a fog, in what a commentator on Kafka calls ‘murky fields of imposition’. The good news is that this case study is less gloomy than Kafka. Resistance is not always futile and there is solidarity that makes space for push back. Before the case, we summarize the debate about systematic reviews and draw some conclusions fromJoseph K’s story.

Systematic Reviews

A 2012 brief from ODI explains that Systematic Reviews (SRs) help answer the question of ‘what works’ in international development policy and practice, a question ‘ever more important against a backdrop of accountability and austerity.’ SRs ‘are increasingly considered a key tool for evidence-informed policy making’. USAID, DFID, CIDA, the World Bank and AusAid are among the development agencies promoting their use. Most SRs have drawn on experimental and quasi– experimental studies of the effects of particular – very specific – development interventions. In the Journal of Development Effectiveness Hugh Waddington and others stress systematic reviews may be less appropriate in relation to broader, less specific issues. Mallet and others (also authors of the ODI brief) emphasize SRs miss context and process, important in international development as compared with medical research from where SRs originate. Birte Snilstveit and others make the case for applying the systematic review principles of transparency, comprehensiveness and systematic rigour to broader policy questions provided the review is more open, interpretative and exploratory. This kind of balanced academic discussion about systematic reviews is not what happened in the following narrative which tells of a lost year of confusion, anger, argument and resistance, involving much energy and time for those involved.

Thus the conclusions this case offers for the Big Push Forward are:

- Internal organisational politics, including loss of face, influenced decisions within the Centre (the grantee) about how to use the artefact.

- The desperate desire to get the grant generated blind compliance, preventing the Centre’s leadership from discussing with the donor about what was sensible and feasible. Those charged with raising money (or maintaining organisational prestige) are more likely to agree to inappropriate conditions than front line staff who know the likely consequences of these conditions much better.

- Power was blocking communications between donor and grantee with Martin B, Do-Good’s Chief for Evidence-Based Policy probably totally unaware of the effects of his recommendation on relationships and hierarchical decision-making processes within the Centre.

- More rigorous methodological alternatives were developed in response to the SR challenge (although these alternatives were rejected by management seeking to comply with the donor’s perceived demands).

- Solidarity enables push backs as evidenced when Joseph K and his colleagues were empowered to say no to the systematic review because other staff approached by the Centre’s management also refused.

- Finding allies within the donor organisation is a good idea in principle but care needed to be taken to avoid irritating the Centre’s management that felt bound to impose the donor’s requirements.

- Appropriating discourse in struggles of resistance is a key strategy as when the visiting expert confirmed that systematic review can be used to describe something rather different from the Director (and Do-Good) understood it. There is not one objective uncontested definition of what any of these artefacts mean.

- There are always surprises that can be opportunities to be seized as in this case, the outside expert commissioned by the Centre’s management took a broad view of what is a systematic review.

STRUGGLES OVER A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

By ‘Joseph K’

Gudrun, Prava and I work at an international development research Centre. My story is based on the 190 emails I received or sent during a year of struggle over a donor requirement that we undertake a systematic review as part of a much larger programme the Centre was negotiating with the donor.

Proposal

Prava, a senior staff member at the Centre was negotiating with Do-Good World Wide for multi-year funding of a gender equality research and policy uptake programme of which an element was a literature review Gudrun and I wanted do about why, despite a substantial body of research evidence, development policies tended to ignore gender-based exploitation within markets. What is it about the global political economy – and the international development sector within it – that usually prevents this evidence being recognized? And what have been the factors contributing to instances of a positive policy response? Prava told us Do-Good’s gender unit liked our idea and agreed to its incorporation in the overall programme. But also, that the programme as a whole would have to be approved by Martin B, Do-Good’s Evidence-Based Policy Chief.

Our Director met Martin B to discuss the approval process. Prava emailed us about the upshot of the meeting, as told to her by the Director.

Our whole programme needs to be about generating, testing and evaluating new policy approaches that will make policy and aid more effective. They want us to sharpen up dramatically in terms of specificity of activity and of what will be delivered. We also need to provide benefit cost ratios on key interventions when available to help them make the economic business case. The Director will undertake to revise our text to make it more instrumental…. And, by the way, your gender-based exploitation within markets is an area where there should be a systematic review.

We were puzz;ed how we could do a systematic review with our political economy question and wondered whether our Director had himself understood what we were trying to do. Gudrun persuaded us to calm down. Reason and common sense was on our side. We proposed looking at a very broad structural reform so this obviously ruled out a methodology used with respect to more specific interventions. At our request, Prava saw the Director again and reported back he agreed that our review should not be a systematic review, provided we sharpened up the draft proposal to demonstrate that it was not lack of evidence of gender discrimination that was at issue but rather why this evidence was ignored. We did this and attached an extensive bibliography representing some of the most well-known research in the field.

Challenge

A week later, Prava emailed us:

Contrary to my understanding of our conversation last week, the Director is still convinced that the systematic review should be part of the proposal. I know you both are deeply opposed to a systematic review as (a) insulting and undermining in terms of the assumption that the it as a problem with the evidence not the politics (b) boring and unnecessary and (c) taking funds away from other and more interesting work. That said, I’m not sure what else I can do to persuade him who seems to be at a take it or leave it position and who says there is no room for pushback with Do-Good. …. I’m now wondering whether if this couldn’t be an activity someone else does rather than you two. There are many other gender people here and it might be a way for a junior researcher to do some Do-Good policy work.

Gudrun replied:

It still makes no sense to do an SR. You may want to check with the Director what precisely would be the question the Review might address. There is clearly another agenda here that I have not been around the corridors of power long enough to pick up on. The Director does not like our part of the programme and he wants something else. Is he aware that Do-Good’s gender team liked it? Why should he decide what we research and how? I have already been involved in a systematic review and am not doing another one. I know what a systematic review is capable of, and it will not answer the question we want to ask. If the Director wants to apply it to another question that is fine as long as it doesn’t take any of the money from the work we want to do.

Prava disagreed

The Director does like it. He thinks gender and labour markets a fascinating topic to explore. He also knows that Do-Good’s gender unit was happy with our proposal. But none of this comes from the Director or from the Gender Unit. It comes from Martin B and it seems as if there is no room to push back on this.

Gudrun and I decided to withdraw from the programme and Prava urgently e-mailed the Director.

I’ve had a series of discussions with Gudrun and Joseph about the Do-Good funded gender programme. They feel extremely strongly about not doing a systematic review. This means that, if we do go ahead with promising a systematic review, it will either have to be funded from a separate source or alternatively Joseph and Gudrun would like to withdraw their idea from the programme. So, I would like to be sure that I have not misunderstood your email from earlier this week, which seems to me to be saying that additional funding will be found for the systematic review? Is this correct? I know you’re busy and have a lot to do, and I appreciate that you are under pressure to meet Martin B’s requests, but I would appreciate your response to this.

He answered instantly.

No need to worry about the systematic review on the resources side. We will find from other sources. Important for Do-Good and I think it will really strengthen your case with people that you are trying to persuade and that actually you might find it really helpful but I appreciate I have not convinced you or the others.

This brief message from the Director reassured us we would still have resources to do our own review and that commissioning a separate systematic review would be the Director’s problem. We agreed to stay in the programme.

Six months later: the politics of inconsistency

The contract with Do-Good had been signed.. The Director had appointed his assistant, Arjun to be the principal contact with the Do-Good administration. Arjun called a meeting to discuss the deliverables. There was an inconsistency in the programme documentation with respect to our part. The narrative section included the power/knowledge question about invisibility to policy but the logical framework, prepared by the Director and Arjun, used instead the question that the Director thought interested Martin B, concerning `costs and benefits of policies to address gender-based market exploitation’. Where did this leave us? There was not much money for our literature review and we realised we couldn’t do it without the additional funds set aside for the systematic review.

Gudrun was very firm that she would not do a systematic review.

I am not sure any of you have done a systematic review before, pls be assured this is really very little like a literature review. Most of the literature you consider to be of high quality will not be considered sufficiently high quality to get into the review, if you follow any of the conventions of systematic reviews. You need to have a protocol for lit searches and lit selection and for data extraction and synthesis and for the review to be considered of high quality all of these have to agreed step by step by an external body – the Cochrane or Campbell Partnership etc. Your past knowledge will be useful but not very much. It is a very mechanical activity but very very time-consuming. I fear it will not produce anything useable for our purposes.

Prava was desperate. The systematic review is a Year One deliverable and it must be done otherwise the Centre’s gender researchers would be in trouble. She approached our colleagues Mirta and Patty who both refused, Patty emailing:

I see the systematic review process as highly problematic precisely because of the criteria and standards (in my view very questionable and deeply power driven) that it forces one to follow.

Gudrun, with her previous experience of systematic reviews, suggested:

‘We should write a page explaining why what Do-Good needs to know about the recognition of an exploitative market is not suited to an SR – because SRs are mainly used to summarise the policy lessons from RCTs, but is an excellent opportunity to test alternative (and more cost-effective) policy synthesis methodologies for issues that relate to the less easily quantified matters of policy reform and women’s empowerment.’

The challenge had sharpened our thinking. We wrote a full-length concept note, setting out a clear methodology about how our non-systematic review would be undertaken. Cheered by this and sure that Do-Good’s gender unit would like it, we were angry to find another hurdle in our way when Prava told us she was not allowed to approach Do-Good directly. Our concept note had to be approved first by Arjun. At a further meeting with him, Arjun ruled that despite our question having been agreed with Do-Good’s gender unit the year before and also included in the narrative of the agreed programme documentation, it was the log frame against which the Centre would be held accountable. And any change to the question as it appeared in the log-frame would have to be cleared with Do-Good.

Gudrun was furious – she had spent much creative effort on the concept note – and stormed out of the meeting. She sent Prava an angry email calling it quits. Prava urged her not to do so.

There is a very good chance that Do-Good will come back to us and say they are happy with the question and go ahead in whatever way guarantees its rigor and robustness. If we have buy in from Do-Good, then why not pursue an area of work that you have invested a great deal in and are passionate about? Hang in there until we see what happens with Do-Good.

But Gudrun was not mollified.

As Arjun knows, I dispute the idea that there has been a change in the question. There was an inconsistency in the proposal. To go to Do-Good saying that we want to change the question would not only be inaccurate it would be non-strategic. However my time is too precious to continue to argue the point. If Do-Good don’t agree the question we are proposing I am very happy to leave it to whomsoever wants to undertake the Director’s formulation of the question, but they will not include me. My involvement in this programme will be over.

Two weeks later, the Centre was visited by the head of Do-Good’s gender unit. Prava showed her our concept note for a non-systematic review. She reported back to us joyfully that the she really liked our approach. The next day Prava got a confirmatory email that the gender unit’s immediate line management was also happy with our original question and it was OK for us to do a ‘thematic’ rather than a ‘systematic review’.

Alas, our problem was no longer with Do-Good but with our own management. Arjun was angry with Prava for talking directly with Do-Good. It was for the Centre to decide whether a systematic review should be undertaken, not Do-Good’s gender unit.

Re-defining the concept

On advice from a colleague of his who had recently done a systematic review (out of 28,000 studies of possible relevance only one study was regarded as sufficiently robust to be treated as reliable evidence) Arjun invited a well known authority on systematic reviews to come down to the Centre to explain the SR methodology. After that, announced Arjun, a decision would be made as to whether gender exploitation in markets would be the subject of a systematic review. Gudrun had washed her hands of the affair and refused to be involved. I felt I needed to become more familiar with the debates and found an article in a health policy journal that proposed another method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. I liked it a lot. It really had nothing in common with the kind of systematic review that Gudrun and Patty had both experienced and that involved the Cochrane or Campbell partnership. Armed with this article I decided to go to the meeting and see what the visiting expert thought of it.

I didn’t need to cite the article. To Prava’s and my delight, our visitor took the same line, stating that a systematic review was not linked to a particular epistemology and the methodology varied depending on the questions asked. After hearing this, Arjun confirmed we could do our review as outlined in our concept note and using the budget the Director had set aside for a systematic review! Had Arjun after all been secretly on our side while protecting the Director from losing face? Or was his choice of visiting expert a happy coincidence? Who knows? After nearly a year of frustration, tears and despair, of quarrels between friends, sporadic surrender and flares of stubborn resistance, it appeared we had won. But it took up so much of our time! What the hell was it all about? Why do I feel so tired and drained of energy?

There is a further twist to this story. Three weeks’ later, Arjun emailed Prava (who emailed Gudrun and me) that his Do-Good administrative contact had urgently contacted him with instructions that resources from the Do-Good funded programme should not be used for systematic reviews. Apparently this was because Do-Good wanted to be in direct control of anything it funds that is described as ‘as systematic review’. However, Arjun was assured it was OK for us to undertake a ‘thematic review’ of the question under consideration as had been agreed with the Do-Good Gender unit. What conversations had been happening inside Do-Good? Had Martin B changed his mind? Or perhaps it had all been a cock up between different departments in Do-Good? We shall never know.

Comments are closed.

Hi Rick,

It may well have been a typo and perhaps the number should have been 2,800. However I have been having a dig and 28,000 could well be correct! See this blog: Lawrence Haddad:

http://www.developmenthorizons.com/2011/10/when-worlds-collide.html> He mentions being a part of a systematic review that surveyed 14000 papers and came up with 3 that met the inclusion criteria. Large numbers also appear in descriptions of systematic reviews here http://www.esri.mmu.ac.uk/respapers/papers-pdf/Paper-Clarity%20bordering%20on%20stupidity.pdf.

See also http://xn--blls-5qa.de/publications/2011_ECIS-Boell,Cecez-Kecmanovic-Sytematic_Reviews-preprint.pdf.

“Systematic reviews assuming that the execution of a rigorous search strategy will lead to identification of relevant literature seem to confuse search terms with concepts (Fugmann, 2007). What researchers are interested in are certain ideas and concepts of relevance to their research problem, not particular wording used to describe them. Moreover, not only may important search terms be unknown, the meaning of words can also differ between specific areas or streams of research as well as among different authors. This can lead to the retrieval of many undesired documents and a failure to identify a potentially large number of relevant documents. The problem for systematic reviews is then: the more inclusive their search strategy, the more irrelevant documents will be retrieved; the more precise and specific the search terms the more relevant documents will be missed.”

I guess my question is, in the case of this story does the correct number matter or make any difference to the overall analysis of what happened and conclusions reached? I am not sure it does?

This discussion of ours may be symptomatic of a wider body of differences in approaches to the nature of “evidence”.

– the figure of 1 in 28000 is quoted but then a proviso is added that its not clear whether the correct figure matters or not. So why quote the figure in the first place? Was it just for rhetorical affect? Take an extreme example and then show how ridiculous it is.

– re Hadad’s experience: Okay we now have two examples. I would give these more attention IF someone could tell us what happened next. Was a systematic review then based on 1 document out of 28000, or 3 out of 14000? Or did the authors recognise the folly of doing so and then try a different approach? Or if they did go ahead did they give good reasons for doing so?

We have a reply now from Joseph K about Rick’s question. He had mistakenly thought that a colleague had been involved in this systematic review in which 27,999 out of 28,000 studies were rejected but on checking back through his 190 emails on this case, he found that the colleague was in fact citing a review that he had come across in which this happened. Here is the reference http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=3208

The more important point for me I guess is that Joseph K was hearing and reacting to hearsay as is often the case in such a chain of events when rumours fly around. Those involved were learning that systematic review searches producing large numbers of potential sources, with few that stand up and this was one of the grounds of their objections. The actual analysis of the story is focusing on their perceptions and actions which arguably are important to understand in the politics of evidence?

This is a late reply to CathyS January 9th 2013.

1. I checked the source referred to. It is interesting to note this statement on that web page: “The searches identified more than 28,000 records. As expected, the vast majority of these were not relevant for this systematic review.” My reading of this was that rejections were not because of differences in methods used, but because of irrelevance of content, in the same way that I in effect reject 99% (x million) search records every time I do a Google search on some topic. In fact its hard to imagine any field of development where there are anything like 28,000 relevant studies, using any conceivable kind of methodology.

2. In her second paragraph Cathy claims that “Those involved were learning that systematic review searches producing large numbers of potential sources, with few that stand up and this was one of the grounds of their objections.” is very questionable. In practice it seems that that they were taking a fairly casual attitude to the meaning of the evidence they were coming across. Of more concern, is the final sentence that seems to imply that such details are irrelevant anyhow, because what matters is people’s “perceptions”. Yes, subjective reactions matter, but so does evidence that contradicts those views.

Yes, it is not uncommon to find large numbers of studies rejected during the process of a systematic review. But the rejection of 27,999 out of 28,000 is literally in-credible.

I am still waiting for the author(‘s) to back up these figures

Re “On advice from a colleague of his who had recently done a systematic review (out of 28,000 studies of possible relevance only one study was regarded as sufficiently robust to be treated as reliable evidence) ”

I don’t believe this statistic, but I am ready to be convinced otherwise,

IF

the author(s) can provide some verifiable evidence of this claim

I don’t find the 28,000 studies figure suprising. Have a look at the SRs published on the 3ie website. In several the only real conclusion is the need for more robust research because there were not enough studies (read RCTs) worth reviewing.

Naomi/Rick, I think a few points are worth noting here, the most important being that searchers typically cast the net widely to ensure important studies are not missed, which means that the vast majority of the 28,000 shown in ‘PRISMA’ flowcharts will be irrelevant to the topic area, and are indeed discarded at the title stage of the search. [Because of this confusion, I’d personally be in favour of only reporting figures for full text extraction onwards, but don’t tell anyone]. It is at the few hundred full text papers identified where I and 3ie colleagues agree there is a big problem that needs addressing in terms of making use of quality development research.

While I must stress that no 3ie SRs have been restricted to RCTs alone, the majority to-date have been limited to counterfactual evaluative evidence (experiments and ‘quasi-experiments’). As we state on p.364 of our tool-kit paper here http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/19439342.2012.711765: “The theory-based approach propounded by 3ie does require that studies without credible [couterfactual] designs are excluded from the synthesis of causal effects. However, analysis of the rest of the causal chain requires other types of evidence. And this evidence is thin in studies that are included because of rigorous impact evaluation designs.”

We are experimenting with approaches to draw on the fuller range of development evidence – primarily qualitative evidence, and other important evidence such as on targeting – in our review of Farmer Field Schools interventions, which we are publishing with the Campbell Collaboration early in 2013 (http://campbellcollaboration.org/lib/project/203/). We are also encouraging 3ie grantees and Campbell Collaboration International Development Group authors to do the same.