Reflection on politics of evidence debate

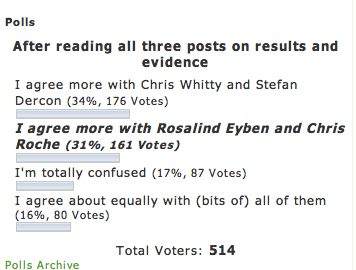

I have been reflecting on the recent ‘wonkwar’ (debate amongst experts) ‘about ‘the political implications of evidence based approaches’. The debate generated considerable interest and activity in the twittersphere; some brilliant comments and quite a large poll that yielded perhaps unsurprising results?

Excellent comments by several people that I cite here, view reminded me that the Big Pushforward’s agenda extends far beyond the realm of evaluation practice and is broadly concerned with the production and use of knowledge by the development community. Several remarks also emphasised that the Big Push Forward needs to articulate its position on ‘evidence’ more clearly

‘Not sure what troubles me most. The twitterati’s inability 2 see the message or Roche & Eyben’s inability to express it’

It became apparent our critique of the ‘discourse of evidence’ was being read as being anti-evidence! Nothing could be further than the ‘truth’. We are critiquing the use of the term ‘evidence’ as a particular discourse that influences what is thinkable and do-able in the politics of development. Inequities in power and voice mean that only some approaches to knowledge are judged acceptable and when these are called ‘objective’ it makes them unquestionable.

As David posted,

‘We all want evidence, it’s a question of whether the current framing of “evidence-based” is distorting what types of evidence we gather and value.’

Our critique of “objectivity in social sciences” is not an argument in favour of bias, it is a call for more explicit acknowledgement of the underlying values and theories – ‘world view’ – that characterize different approaches to evidence, I take a critical realist position to knowledge; my assumption is that I cannot know the world of social relations (the matter of development) independently of how I understand it and relate with others. As a consequence all questions explored and knowledge produced are ‘partial’. Halima Begum observes:

“None of us can ever remove ‘bias’ from research/interventions altogether – positivist models assert objectivity of ‘hard’ data, but even that ‘hard data’ is interpreted by a subjective mind, usually a researcher who will have some baggage due to background/upbringing, and if no personal baggage, some institutional incentives to interpret the data one way or another.”

Medical knowledge has improved human wellbeing through methodologies like random control trials evidence. However, these are not generalizable to all development issues, particularly the challenges of social transformation in different historical and social contexts. Hakan Seckinelgin summed up some key issues:

“When the attempt is to test ‘if something or what works’, it is not a simple case of observing X leads to Y. These tests will have to explain: a) why what is being tested by ‘us’ is relevant for the context (otherwise we are using people to test our ideas for our purposes); b) ‘why’ something works or not: what are the conditions under which an effect is emerging. Things emerge as a result of many causal interactions independent of what we can see and know, is there a way to know and consider these c) what is in our methods which will allow to think what worked here might also work somewhere else.

Methods will not produce results independent of how they are deployed to answer particular questions. Sally Brooks noted the danger of evidence- based discourse obscuring the politics of research processes themselves. Hakan wisely recommends we need to be more aware of power.

“If we are interested in ‘proper evidence’ one needs to answer the following questions: who are ‘we’? What is the definition of ‘properness’? And whose interests a given ‘properness’ definition will satisfy?

As Hakan says, methodological discussions obscure that different types of evidence are used for particular purposes, for example to “present objective facts to leverage others to act on what they want them to do.” We need to be aware of the socio-political interests and ideological positions of those involved in the debates about the methods used to ‘generate evidence’, including examining how ‘evidence’ is used or rejected by policy makers in the broader context of often political decision-making processes.

Questions raised in the wonk war highlight the importance distinguishing between evidence BASED policy and evidence INFORMED policy – the latter is more explicit about the world-view biased production and political use of knowledge. As Enrique Mendizabal and Martin Belcher argue evidence informed policy also requires “effective public debate of that evidence and by extension building the capacity of policy making stakeholders to demand, access, evaluate and use evidence.” This includes evidence that is rejected.

Robert Stone reminds us to heed Patrick Kilby’s recommendation and remember that debates, like development interventions, take place in historical contexts and complex systems. He notes how far the development community has come in its “reflexivity and in our understanding of political economy since the days of the Washington Consensus and the even more paternalistic period that preceded it.” This is so true. Debates are not about winning polls. They are about provoking reflection on our assumptions. If you want to continue to participate in this discussion, please register for the Politics of Evidence conference. It promises to be a lively event!

Comments are closed.

I’ve also been following this discussion from the perspective of the role of knowledge managers/knowledge brokers. for me the issue is not whether we need to collect more and better evidence (we clearly do) but that we need to understand the limitations of the evidence we are able to collect and also take more account of how it is disseminated and used and be realistic in understanding that “scientific” evidence, whether quantitative or qualitative, is in reality only one part of policy and decision making – and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Here’s a blog post I juast wrote on this in reaction to the Gates annual letter which essentially is advocating for more measurement as the next big idea for development http://kmonadollaraday.wordpress.com/2013/02/05/in-measurement-we-trust/

Thanks Ian for drawing attention to these really useful blogs. I find them particularly interesting given that the Gates Foundation’s values include:

” Innovation

We believe that many of the most intractable problems can only be solved through creative and innovative solutions. In pursuit of these, we embrace risk and learn from failure, helping others to avoid the same pitfalls in future. We strive to remain focused, strategic and calculated in our risk-taking, as we challenge convention, question assumptions and confront stereotypes.”

I have been appropriating this in consultancy work with other donors, recommending they too more explicitly seek to learn from failure….(whilst also acknowledging the political challenge of doing so). It would be disappointing if Gates doesn’t practice what it preaches….

(Incidentally, Alnoor Ebrahim has an upcoming paper on NGO accountability that has a great framework for exploring this tension between learning from failure and being accountable to funders. Do keep a look out for that.)

Your reflections on measurement are bang on. I am particularly interested in Goodhart’s Law – its popular articulation by Margaret Strathern being: “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” I wonder what we in the aid sector can learn from several reports about the effects of targeting in the UK: the The Ofqual findings about the English O Level fiasco last year; the Francis Report on the Staff’s hospital; and Daniel Bear’s research on the effect of top down targeting in the police?